(NEW YORK) — When Katharine Lee, a postdoctoral research fellow at Washington University in St. Louis, and Kathryn Clancy, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, each say they experienced unexpected menstrual cycles after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, they did what researchers do and began to collect data.

Clancy conferred with Lee, who said several colleagues had also reported differing menstrual symptoms, and issued a single tweet in late February explaining her own symptoms and asking if anyone else had experienced anything similar.

Three months later, Lee and Clancy say more than 80,000 people have documented their experiences in an online survey they collaborated on examining short-term vaccine side effects related to the menstrual cycle.

“We’ve gotten so many messages where people got a heavier period or a period they weren’t expecting and were frantically Googling to see what was wrong with themselves,” Lee told ABC News’ Good Morning America. “And they stumbled across our survey and we were the only people saying, ‘Hey, did this happen to anyone?'”

Today, with millions of Americans already fully vaccinated, scientists and doctors still don’t know exactly why — or even if — vaccines might impact menstruation.

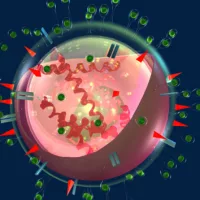

Unexpected changes to a woman’s period can happen from an inflammatory response or because of stressful events. And experts agree any changes to menstruation are likely to be temporary, and there is no reason for women to worry, including when it comes to fertility.

But women including Lee and Clancy, who experienced the menstrual changes themselves, say the lack of research and interest in the vaccines’ impacts on people’s menstrual cycles is a sign of what happens when women are left behind in medical research, as they have historically been.

“We owe it to people as researchers to understand that experience,” said Lee. “Much as people were recommending to have Tylenol on hand in case you get a fever [after the vaccine] and to make sure your schedule is clear in case you get fatigue and a headache, this is just something that people should be informed about what could happen to them so they can react appropriately and not be scared.”

“This again speaks to the importance of inclusion and equity within scientific research spaces,” added Clancy. “If we hadn’t had all of these bodies that had periods and had uteruses having these experiences, having this expertise, we might not have put all of this together.”

The experiences of tens of thousands of women, as documented by Lee and Clancy, came even as the researchers behind the COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials made an effort to have diverse participants in the trials to match the world’s demographics. In the clinical trials in the U.S., about half of trial participants were people who identified as female.

That represents a stark change from medical research of the past, when women have been historically underrepresented.

As recently as three decades ago, women were not required to be included in medical research.

In the 1970s, for example, the first clinical studies on the effects of estrogen — the sex hormone responsible for female physical features and reproduction — were done on men.

It was only with the passage of the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act in 1993, signed into law by then-President Bill Clinton, that the inclusion of women and people of color became required in federally funded research.

“The prevailing tradition in science for many, many years was not to include women in clinical trials,” said Carolyn M. Mazure, professor and director of women’s health research at Yale University. “That tradition left us with a very significant knowledge gap on the health of women, and that’s the tradition that we’ve been trying to reverse for all these years.”

While the 1993 law is described by Mazure and other experts as a “benchmark” in women’s health research, it was only five years ago, in 2016, that the National Institutes of Health, the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world, began to require the inclusion of female vertebrate animals in laboratory studies.

The reason for the lack of medical research on women was a combination of concerns about fertility and a knowledge gap on the differences between men and women, according to Dr. Janine Austin Clayton, director of the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Heath, which was established in 1990 out of concerns that clinical decisions were being made for women based on the findings of studies on men, according to the office’s website.

“Many, many years ago, this did not come from a malevolent place,” Clayton said of the disparity. “Women were not included in clinical research as a way to protect them, No. 1.”

“There was concern about including women who might become pregnant in clinical research and that was understandable,” she said. “With a motivation of protecting women, protecting fetuses, there was an emphasis on men as research subjects.”

“No. 2, it wasn’t known that findings from studies on men shouldn’t be applied to women,” Clayton added. “That information wasn’t available. That was not common knowledge at that time.”

Thanks to decades of research and a more recent course correction, scientists today know that “sex operates at every level” of the human body and have taken steps to adjust their research accordingly, according to Clayton.

“We now know that overreliance on male animal models in our preclinical research has resulted in us knowing less about female biology,” she said. “Since we know those things now, we need to do better. We need to design our studies differently.”

Why research on women’s health matters

The major difference it makes when women’s health is researched was seen earlier this year in a study that found that doctors may have been using the wrong metric for women’s blood pressure.

The study, published in February in the journal Circulation, found that while less than 120 millimeters per mercury may be within the normal range for systolic blood pressure for men, the target systolic blood pressure for women should be less than 110 millimeters per mercury.

The study was funded in part by the NIH’s Office of Women’s Health Research.

“Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for men and women,” said Clayton. “If you imagine we’re not treating women that have a blood pressure of between 110 and 120, that means we’re not preventing heart attack, stroke, peripheral artery disease in those women.”

“What could happen if we did go ahead and get women treated earlier? How many more years of healthy life could they enjoy?” she said.

How the historic lack of research on women’s bodies plays out in women’s everyday lives can also be seen in the stories of women who say it takes them years to get a diagnosis for conditions like endometriosis, which affects an estimated six million women in the U.S. and can take as long as a decade to be diagnosed, and for autoimmune diseases, which affect more women than men.

It can be infuriating for women to learn how much ground there is left to cover to simply catch up on the research, a revelation that often comes as women are in their childbearing years and trying to catch up themselves on what they aren’t often told about their own fertility.

“You can always see when people have that ‘aha moment’ about their own reproductive health and about the state of women’s health research,” said Afton Vechery, whose “aha moment” led her to co-found Modern Fertility, a reproductive health company that provides personalized fertility information. “It’s like, ‘Oh my gosh, what are we going to do about it?’ and the second [reaction] is anger.”

Anger over her experience getting a diagnosis for what ended up being rheumatoid arthritis is in part what motivated author Maya Dusenbery to write Doing Harm, which looks at the effects of the lack of research on women’s health, including how long it can take to be diagnosed.

“When women are dismissed or end up going to multiple doctors before they’re properly diagnosed, we don’t currently have systematic feedback systems in place so that those doctors learn that the patient they thought was just stressed was later diagnosed with an autoimmune disease,” said Dusenbery. “It creates this self-fulfilling problem where the stereotype they held of that patient never has the opportunity to get revised.”

Dusenbery said she also found in her research how much we’re still experiencing the after effects of a decades-long absence of research on women.

“It takes a long time for study results to be published and for medical knowledge to filter out,” she said. “[It] really means that even today, even the very best doctors who have gotten the best education just aren’t as equipped. A lot of the basis of our biomedical knowledge is still skewed to knowing more about men.”

Dusenbery and other experts say the coronavirus pandemic has provided a spotlight for both the biological differences between men and women, and how far behind women are still are when it comes to science’s knowledge of their bodies.

More men than women, for instance, have died of COVID-19 during the pandemic, but women seem to be more affected than men by long-term complications of the virus.

More than one year into the pandemic, there is now data showing the increased risks the virus poses during pregnancy.

Yet, pregnant people were not actively recruited for COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials. It is considered typical — and many argue ethically appropriate — to study an unknown substance first in healthy adults and then progressively in broader and broader populations, like children and pregnant people, but the lack of data on vaccines has led to confusion for some people who are pregnant or in their childbearing years. Pfizer did not begin trials on its vaccine in pregnant women until February.

“If we could include pregnant women earlier in the process of vaccine development and gather as much research and data from them, as on everyone else, we would be in a position to be able to provide evidence-based recommendations, even in a pandemic where things have moved very quickly,” said Clayton. “In the future, if we could have what I call ‘sex and gender aware studies’ and be thinking about that as we develop it, maybe we would use different dosages of the vaccine and be able to test that.”

The race to catch up

In a sign of the emphasis increasingly being placed on women’s health research, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health has teamed up with Apple and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) for a first-of-its-kind study using menstrual cycle tracking data from iPhones and/or Apple watches.

The purpose of the study, which began in 2019 and includes over 10,000 women, is to examine women’s menstrual cycles and their relationship to several health conditions.

“This a grossly understudied area of medical research,” Dr. Jennifer Ashton, ABC News chief medical correspondent and a board-certified OBGYN, said in March, as some of the study’s first results were released. “This is really going to uncover a whole new possibility in terms of understanding what in the field of gynecology is considered a vital sign [because] it’s a window into the overall health of a woman.”

“This is something that obviously hundreds of millions of women around the world are going through on a regular basis, oftentimes in silence, so collecting this data is key,” she said.

As the leader of the U.S. government’s effort to promote women’s health research, Clayton said her goal is to make studying sex and gender as “automatic as looking right or left before you cross the street.”

“I would say that it won’t be enough until it’s done automatically,” she said. “We’re not there yet and there’s still a lot of ground to make up because we were behind.”

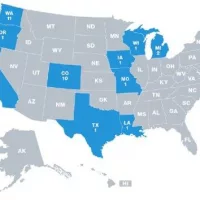

Clayton says it’s a sign of progress that today over half of the participants of NIH-supported research are women.

She said she is also excited by new research coming to her desk that is a result of the 21st Century Cures Act, which was signed into law by then-President Barack Obama in 2016 and, among other things, expanded sex and gender-based results reporting requirements in NIH-funded studies, according to the Office of Women’s Health Research.

“Most NIH studies take about five years so we’re now seeing the publications coming out of those studies that were done out of this new policy,” said Clayton. “It’s amazing what people have learned, what new discoveries have been made because they have studied males and females in their preclinical work.”

“Women should be kept in mind all the way and at each step of the way,” she said.

Clayton is also focused on moving clinical research forward to a point where study results are automatically reported by sex, which data shows female scientists do more often.

“They’re more likely to study both male and female animals and they’re more likely to report results by sex,” she said of female scientists. “They have an impact in what they choose to study, what they do and how they report it.”

Clayton is joined by other experts in stressing also that in order to move forward, women’s whole health must be considered, not just their reproductive health.

Heart disease, for example, not breast cancer or gynecological cancer or maternal mortality, is the leading cause of death for women in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Any condition that a woman can suffer is women’s health,” said Mazure. “Reproductive health is not all of women’s health.”

“In so much of the research, that paternalism is that we think that fertility is the most important thing in a woman, or anyone with a uterus,” added Clancy. “I don’t know, but there are times that I would rather just be alive.”

Clancy and other experts say that by also focusing on the whole health of women, researchers will take a much needed step toward making women’s health research more inclusive.

“People who are gender queer, trans, nonbinary have some of the highest rates of hate crimes, some of the highest rates of suicide, some of the highest rates of being unhoused and yet they keep getting thrown out the window because we care so much about characterizing this around women and around fertility,” said Clancy. “A big step that we need to make is to start to detach some of these things. Gender identity absolutely matters to biology, but not in the way people think.”

The NIH established the Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office in 2015 to lead the coordination of sexual and gender minority-related research.

As a result, more studies are collecting sex and gender identity information, according to Clayton.

“That’s an area of real growth in the last five years and an area of continued focus for NIH,” she said.

Copyright © 2021, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.