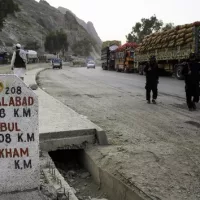

(LONDON )– As Jahanzeb Wesa fled toward the Pakistani border in the middle of the night, he wondered if his career defending human rights would help protect him now that he was a refugee himself.

A 28-year-old Afghan journalist and women’s rights advocate, Wesa said he was attacked by a Taliban fighter while covering a women’s rights protest just after the fall of Kabul in August 2021. If he didn’t make it across the border, he said, he knew he would likely be killed.

“We worked for 20 years for a better future for Afghanistan,” he recalled thinking. “Why did we lose everything?”

But arriving in a new country brought no sense of safety.

Following the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan, some Afghan journalists said they have been in limbo waiting for humanitarian visas while living in exile in Pakistan, where they fled across the shared border when Kabul fell.

The Taliban’s violent suppression of criticism, along with draconian crackdowns on women’s rights, meant journalists who stayed in Afghanistan were at constant risk of being detained, tortured, disappeared or killed.

In Pakistan, unable to legally work and threatened with deportation through government ultimatums and face-to-face interactions, some Afghan journalists applied for visas from countries that promised to help Afghan refugees.

Almost three years later, many said they still have not received a decision.

In the meantime, their prospects in Pakistan are dire, several told ABC News.

Life in Pakistan

Several Afghan journalists living in Pakistan told ABC News that their fear of deportation is omnipresent.

Khatera, a journalist from northern Afghanistan who asked ABC News not to publish her last name for her safety, fled to Pakistan in April 2022 after the Taliban raided her newsroom, destroying radios and TVs.

“After that,” she said, “everything was a nightmare.”

Like many Afghan journalists in Pakistan, Khatera arrived on a tourist visa she had to renew every six months through a private travel agent. Visa renewals were sometimes denied without reason, and officials often asked for bribes, she said.

The Pakistani government did not reply to a request for comment.

Housing, health care and transportation in Pakistan can be prohibitively expensive for Afghans, whose tourist visas don’t allow them to work. Many rely on depleting savings, support from family members, or under-the-table jobs, according to those who spoke to ABC News. Given the economic strain, the biannual visa fee and the corresponding bribes present significant burdens, they said.

But not having proper documentation can bring serious consequences. “Anywhere you’re going, the police are asking about your valid documents,” said Khatera. They sometimes conduct nighttime home check-ins and try to deport those who can’t provide valid papers, she said.

Those disruptions to daily life don’t appear to be unique to journalists. A 2023 Human Rights Watch report declared a “humanitarian crisis” of Pakistani authorities committing widespread abuses, including mass detentions and property seizures, against Afghans in Pakistan. Over a month and a half, the report said, Pakistani authorities deported 20,000 Afghans and coerced over 350,000 more to leave on their own.

Afghan journalists regularly receive death threats from the regime at home over social media, Wesa said. “If I’m deported to Afghanistan,” he said, “the Taliban is waiting for me.”

“No journalist has been condemned to torture, disappearance, or death by the government of Afghanistan,” said a spokesperson for the Taliban-run Afghan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, adding that “all citizens of the country are equal in the eyes of the law regardless of their position and profession.”

Some journalists said they also face a widespread mental health crisis. Rahman, an Afghan journalist who asked ABC News to use his middle name due to what he described as ongoing threats from the Taliban, struggles with worsening depression and anxiety. He said he fears for himself and his family, still in Kabul.

“It’s daily mental torture,” he said.

An endless wait

The conditions in Pakistan have spurred many Afghan journalists to apply for humanitarian visas from the U.S., Australia, the U.K. and other European countries. Yet, some have not heard back for about three years.

Wesa applied for an Australian humanitarian visa on Jan. 4, 2022, six months after he arrived in Pakistan. He supplemented his application with support letters from Reporters Without Borders, Amnesty International and other nongovernmental organizations stating his life was at risk, he told ABC News.

More than two years after filing his initial application, he has received a confirmation of receipt but no further updates, he said.

A departmental spokesperson from the Australian Department of Home Affairs said they “expect it will take at least 6 years from the date of receipt for processing to commence on [the applications] lodged in 2022, 2023, or 2024.”

“We will wait – there is no other way,” Wesa said in response. “I hope they help us as soon as possible.”

“Day by day, I’m faced with depression and health issues,” he said. “My only hope is that Australia will save my life.”

Rahman, who reported on women’s rights in Afghanistan, is saving up to apply for a family visa from Australia, where his fiancée lives. The process costs over $9,000. He said he believes a humanitarian visa application will not receive a response.

Requests for help from the French embassy and the U.N. have also yielded no results, he said.

“I believe these countries have always been for freedom and for democracy. They can help out,” he said. “I just wonder why it takes such a long time.”

Khatera applied for a visa from the Swiss embassy. It took a year and a half to receive the file number, she said. She was told she needed close relatives in the country, but otherwise, they would likely not be able to help.

“I’m getting depression,” she said. “I’m just trying to fight.”

Every Afghan journalist in exile interviewed by ABC News said they continue to receive threats from the Taliban over social media and fear for their lives every day.

The Taliban denied sending the threats, saying “the government and officials of Afghanistan have not threatened any journalists.”

Broken promises

Afghan journalists waiting in worsening conditions for responses to their visa applications said they feel that Western countries have broken their promises to help Afghan refugees.

The United States expanded a resettlement program for Afghan refugees in 2021 to include journalists and humanitarian workers who had helped the United States. However, as of 2023, The Associated Press reported that only a small portion of applicants had been resettled.

The U.S. State Department did not respond to a request for comment.

The Afghan Pro Bono Initiative, a partnership providing free legal representation to Afghan refugees, published a 2023 report entitled “Two Years of Empty Promises.” The report found that the U.K. resettlement programs for Afghan refugees were fraught with delays, understaffing, administrative hurdles, narrow eligibility and technical issues.

Earlier this year, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and other NGOs called on Western countries to adopt prima facie refugee status for Afghan women and girls, which would grant refugee status without the need for individual assessments, potentially streamlining the application process and decreasing lengthy wait times.

Despite the dragging wait times and the pervasive hopelessness, many of the 170 Afghan journalists in exile in Pakistan continue to speak out against the Taliban.

Wesa’s X account includes frequent posts about Afghanistan — legal updates, protest videos and women singing to resist what they describe as draconian Taliban policies.

“In any country, I will stand for Afghan women,” he said. “I will risk my life for them.”

Copyright © 2024, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.