ABC NewsBY: JON SCHLOSBERG and DEBORAH ROBERTS

(CHICAGO) — Under the grass it is barely noticeable: an unmarked grave covering one of America’s “Hidden Figures” for nearly a century.

You probably have never heard her name, but Nancy Green has likely been in your kitchen before. Green created the Aunt Jemima recipe, and with it, the birth of the American pancake.

“Her face on the box, that image on the box, was probably the one way that households were integrated,” Sherry Williams, president of the Bronzeville Historical Society in Chicago, told ABC News.

Long before she pioneered that famous mix, Green was born into slavery in Montgomery County, Kentucky.

After the Civil War, she moved to a deeply divided Chicago, becoming a strong voice at Olivet Baptist Church, the city’s oldest black congregation.

“This church was noted for its work to shield those who had escaped slavery, who arrived here in Chicago because there were many slave catchers in Chicago still pursuing people who were of African descent,” Williams said.

Williams has been shining a light on Green’s story for more than a decade, giving underground railroad tours of the neighborhood. In the past few years she finally identified the exact location in Chicago’s Oak Woods cemetery where Green was buried.

“I mean who else has experienced slavery and then walked through all of the experiences of America, Jim Crow, segregation, lynching,” Williams said.

To Williams, Green “is that essential worker that we should salute from today in times to come.”

To get Green a headstone, Williams needed the approval of one of her descendants.

After a long search, Williams finally found Marcus Hayes.

“When I found out about it, to be honest, I was shocked, and excited at the same time. Living in the United States, some African Americans, as you may know, it is hard for them to go that far back, to get who they’re connected to,” Hayes said.

Hayes remembers hearing stories of Green’s pancakes.

“It was so good that the boys would now tell everyone … the milling company heard about it … they came and sought her out,” Hayes said.

And just like that Aunt Jemima was born. It made its debut at the World’s fair in Chicago in 1893.

As legend tells it, Green sold 50,000 boxes of the now famous pancake mix.

“She was the trusted face. Back then, you know, anybody who would look at an African American woman cooking, they knew that they can trust her cooking, that she could cook,” Hayes said.

But for all those years, ads by Quaker Oats for Aunt Jemima never mentioned Green.

Green lived until the age of 89 but died after being hit by a car in Chicago in 1923.

After her death, female ambassadors hired by Quaker Oats continued the legacy.

Lilian Richard was one of them.

Richard put her small Texas community on the map and as a result, Hawkins, Texas, is considered the pancake capital of the state.

Unlike Green, Richard has her own headstone and a plaque in Hawkins.

The town also holds a pancake breakfast every year.

“One of my cousins, she would dress up in the same type of clothing that my Aunt Lillian had … she would get up and tell the story to those that attended the ceremony that did not know,” Vera Harris, a descendent of Richard’s, said.

Harris added, “I believe that some people may have thought that those faces were not real.”

Now Harris and Hayes say those real faces, and real stories, are in danger of being erased.

In June, PepsiCo, Quaker Oat’s parent company, announced that the Aunt Jemima brand would be phased out by the end of September.

The sudden news in the midst of this country’s “racial reckoning” shocked both families.

“I was, I was taken aback. I was really shocked. I knew people didn’t realize that those were real people and, you know, to phase them out, would kind of erase their history,” Harris said.

Hayes worries about Green’s legacy when the brand goes away.

‘She’s just not a character … I really want her legacy to be told. That this is a real person. And this was her recipe. And she fed the world from her flapjacks,” he said.

While some people might view the image of Aunt Jemima as antiquated or insensitive, Williams does not see it that way.

“No time ever have I heard anyone in my community say that this image was one that was derogatory. So I don’t know where that sentiment is coming from,” she said.

In a statement to ABC News, PepsiCo said, “This is a sensitive matter that must be handled thoughtfully and with care. We respect the women who have contributed to our brand story and will approach our rebranding with their heritage in mind.”

Pepsi also announced plans to commit $400 million to various causes to help with diversity but so far has not contacted Hayes or Green or announced a definitive future for the longtime brand.

Hayes and Harris both hope Green and Richard are part of that future.

‘We don’t know what it could be called as long as she is somewhere in the mix. Call it ‘Nancy Greene’s,'” Hayes said.

She went on, “It’s not about the money, this is about the truth.”

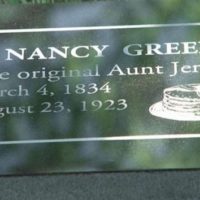

After a decades long push, Williams was finally able to raise enough money to give Green a proper headstone and marker.

Headstone artist Mark Hunt carefully etched a face that will now be preserved for generations — a face America is finally getting introduced to all these years later.

Williams and Hunt are planning a plaque at Olivet Baptist Church as well– with more honors to come.

The headstone will officially be placed over Green’s grave on Sept. 5 after she laid in anonymity for nearly a century.

“I think for me, it gives me the courage. It gives me the motivation to push forward and make sure that you do something great in this world, that you leave a mark that people know about you,” Hayes said.

Copyright © 2020, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.